By Randy Williams

How to account for climate when picking out windows

Understanding the local climate is key to selecting the right windows for your project. Guest contributor Randy Williams explains what you need to know.

Where do you live? Is it cold or hot, wet or dry, or something in between? I live in an area that is considered cold and moist, Northern Minnesota. My climate is much different than Tucson, Arizona or Kansas City, Missouri. Because of the climate differences, some of my choices in building materials will be different, including my choice of windows. Windows should also be chosen with local climate in mind.

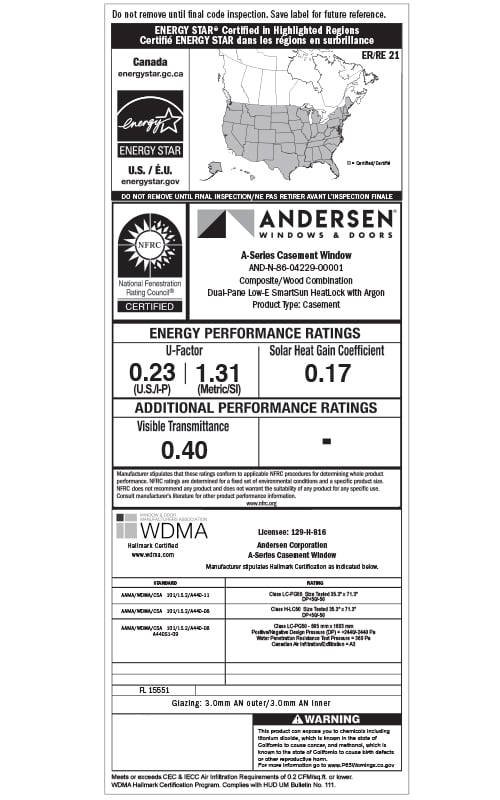

In this piece, I’ll help you understand how climate affects code, what measures you should look at when assessing windows for your climate, and how window selections can improve performance.